Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Silk Way Rally doesn’t quite hold the same prestige as it did in the mid-2010s. However, the height of the SWR—and arguably still in the eyes of a good chunk of rally raid enthusiasts today—effectively made it a “summer Dakar Rally”. Held every July, it is among a few marathon rallies that span at least two weeks and occasionally crosses borders.

The Silk Way wasn’t the first time Russia organized an international rally raid. Nearly two decades before the inaugural SWR, when the Cold War was in decrescendo, the Soviet Union sought to host the “MOVLAD”. Although not a transnational race like the Paris–Dakar or the SWR today, it would’ve stretched from Moscow to Vladivostok and followed the Trans-Siberian Railway.

For a country with not much of a rally raid scene at the time, it was a bold move. So bold that for 1990, it felt like a Hail Mary to revitalize a superpower on its last legs. In fact, that was basically what it was.

And the pass fell incomplete.

Racing and Rally Raid in the USSR

Motorsports in the Eastern Bloc was bound to have its quirks. Formula Easter was their take on open-wheel racing in which cars were built using parts sourced from within the bloc or COMECON members. Countries with existing domestic auto industries were naturally better equipped for these compared to others.

This extended to closed-cab series as well. Soviet road racing was predominantly held on freeways because there were no circuits at first, which made organizing a logistical nightmare. It also didn’t help that these races were loooooong: on August 6, 1956, a 700-kilometer stretch of road was closed for a race from Minsk to Moscow and back as part of the Spartakiad of the Peoples of the USSR.[1] Minsk was also the site of the first highway “track” in 1955 with a whopping 40-km course in 1955.[2]

Race officials quickly realized fans got bored from seeing cars pass by then disappear for 20-plus minutes. Once the discipline was refined, it still stood out from the outside world: the most common race weekend consisted of two events, one for formula cars and another for production vehicles, and the combined results of a given pair would rack up points to win the overall.[2]

Racing in these countries was ostensibly for developing the automotive industry rather than the spirit of competition.[2] (It would be easy to make a joke about sports being bourgeois, but the USSR loved that stuff just as much as the filthy capitalists.) The Soviet Union’s Central Automobile and Motorcycle Club gained FIA and FIM membership in October 1956 after a two-year accession, which DOSAAF—a “sports club” that developed vehicles and weapons for the military—head Major General B.F. Tramm heralded for “broad opportunities for strengthening sporting ties, the participation of Soviet racers in various international motorsports competitions, and familiarization with the experience of foreign sports organizations.”[1]

It didn’t take long for them to dip their feet into rally raid when the discipline was being developed in the late 1960s. Soviet drivers had already competed in traditional rallies outside the Union as early as 1958 when four Moskvitchs appeared at the Jyväskylän Suurajot in Finland.[3]

The 1968 London–Sydney Marathon is often considered the start of modern rally raiding, taking cars across 11 countries by land and sea. Avtoexport entered the race with four Soviet crews in Moskvitch 412s, who were among 98 approved of over 800 applicants.[4] Each of them went the distance led by Sergey Tenishev in 20th overall.[5] They continued to appear in various rallies as the discipline grew in the 1970s.

When the Paris–Dakar Rally debuted in 1979, the Soviets weren’t present. Their vehicles certainly were, though.

Cars like Lada and Moskvitch had begun sale in Western countries like France during the decade, and four Nivas took part in the inaugural Dakar with Frenchmen behind the wheel. This practice of Western customers in Soviet cars would be the norm thanks to those like Jacques Poch, who served as the French dealer for Lada.[6]

“Only high-class cars and the best drivers can contend for first place,” Poch told Pravda, the official newspaper of the Soviet Communist Party, in 1986.[6] “Not everyone reaches the finish. Successful participation in the rally is not only the hardest sporting test but evidence of a car’s merits, its calling card. In recent years, the Niva and Lada have regularly been among the favorites.”

In lieu of the Soviets, the rest of the Eastern Bloc was more open to taking part. In 1985, LIAZ entered the Dakar Rally with two 100.55 D trucks, one with an all-Czechoslovak crew led by Jiří Moskal who finished 13th in class. Tatra would join the fray a year later with future great Karel Loprais.

Soviet teams finally appeared at the Dakar for the first time in 1990 with KAMAZ-master. All three KAMAZ-5320 trucks retired with an engine failure, broken crankshaft, and destroyed flywheel (they also had a fourth that didn’t pass pre-race inspection). Vladimir Marchenkov’s #506 was in such bad condition that the team had to leave it in the Mauritanian desert. That truck remained stuck for months and was plundered before KAMAZ and the Soviet embassy could return, where they decided to set it on fire and leave it to be reclaimed by nature.

“The lessons of the first Paris–Dakar Rally for Soviet racers are useful for us,” Pravda‘s Sergei Filatov wrote.[7] “Conclusions will probably be drawn on how to prepare in order to complete the entire route and not repeat some of the mistakes of the latest race that caused the KAMAZ trucks to drop out of the competition.”

In the long term, those lessons translated extremely well for KAMAZ as the manufacturer won the Dakar 19 times in the Truck category and remain a powerhouse today at the Silk Way. In the short term, it seemed the lesson was to… make your own race?

Smirnov and a Declining Empire

April 1990 was a long month for Vitali Smirnov, arguably the worst in a decade. Ten years ago, he faced down a boycott as head of the organizing committee for the Summer Olympics in Moscow and a vice president on the International Olympic Committee. That, he could at least blame on those darn Americans, which he did. Kind of.

Publicly and in recent years as the Honorary President of the Russian Olympic Committee, Smirnov has stated the 1984 Eastern Bloc boycott of the Los Angeles Summer Games was retaliation for what happened four years prior. In 2020, he told TASS the Soviets wouldn’t have done so “if the Americans hadn’t set an example.”[8]

However, in an unpublished memoir, he said the ’84 boycott was far more complex than that. Instead, Smirnov pointed to Marat Gramov, the newly appointed head of the Soviet Olympic Committee. Gramov was an apparatchik who worked on propaganda for the Communist Party’s Central Committee and had very few ties to the sports world; by appointing a leader who was apathetic to sports at best and hated it at worst, a boycott could be easily enforced without worrying that he’d change his mind. Smirnov also alleged that Gramov was paranoid about his job security after the Soviets lost in the gold medal count to East Germany at the Winter Olympics in Sarajevo, and that suffering the same fate in the United States “would be a death sentence” for him.[9]

For the folks who actually oversaw the Moscow and LA Olympics, things were actually quite chummy. Smirnov and LA head honcho Peter Ueberroth had been in close contact figuring out the logistics for the Soviet team until the very end, so much so that when Ueberroth commended Smirnov in his autobiography, the latter was questioned by TsK KPSS.[9] Konstantin Andrianov, another Soviet IOC executive, was felt the LA organizers were “doing an excellent job” when he was asked about them in Sarajevo.[10] Smirnov and Andrianov also opposed IOC sanctions on the United States in response to the 1980 boycott, the former calling them “obviously unacceptable”, and later attended the ’84 Games for a bit before leaving simply because he “had nothing else to do” without Team USSR’s presence.[9][11]

That said, at the turn of the decade, the main issues in the Union were internal. The USSR was going through its worst food shortage since World War II—not famine levels, but bad enough that National Geographic felt the incoming McDonald’s in Moscow wouldn’t be enough to help out.[12]

For Smirnov, geopolitics were at play.

The Soviet Olympic Committee was set to vote for its next president on April 19 following Gramov’s retirement, where Smirnov ran against Nikolai Rusak of the National Sports Committee (who succeeded Gramov at this post) and Yuri Titov from the International Gymnastics Federation (who later withdrew). Smirnov was the favorite due to his IOC role, having served there since 1971, and being the chairman of the State Sports Committee of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.[13] Whoever won would take over a sports apparatus on the decline.

The political turmoil that was gradually bringing down the Iron Curtain held ramifications for the SOC and the larger Soviet sports committee Goskomsport too. Outside the USSR, Ceaușescu had fallen in Romania, the Berlin Wall was on its way down, and Slovenia and Croatia were set to hold their first elections in decades and break away from Yugoslavia. Within, independence movements were growing in places like the Baltics.

In tandem with their efforts to regain sovereignty, these republics formed national sports federations separate from the central Soviet system. Teams outside the Russian SFSR also broke away to start their own national leagues and even pondered how to get Western sponsors to back them. The Georgian Soccer Federation, for example, seceded from their Soviet counterpart ahead of the 1990 season while Lithuania was fast-tracking the same in basketball.[14]

This was unacceptable for the SOC. Besides the obvious political implications, it would deal a serious blow competitively because of how crucial the other republics were for the USSR’s national teams. After all, the Soviet basketball team heavily relied on players from the Baltic states, which were a basketball hotbed even before Soviet occupation and remains the case today. Smirnov tried to equate the effects of Baltic independence on sports to if the IOC allowed Quebec and Catalonia to establish their own National Olympic Committees, pleading that they must “compete as one Soviet team” while saying he was fine with them having more autonomy.[14]

By 1990, the sports situation had gotten so bad for Moscow that the Soviet Olympic Committee quietly dropped the “National” from their name since it made no sense when it consisted of multiple NOCs. Smirnov tried to stay optimistic and hoped “we will survive. You realize what is going on in other Eastern European countries, and it is a pity. Sports are an important part of Soviet life. People here don’t want to lose at big sports.”[14]

Hoping to keep the ship somewhat afloat, Goskomsport offered a compromise the week of the SOC election: they would organize the leagues themselves as long as the Kremlin footed the bill. Even then, nobody expected infrastructure to actually improve; Alexander Kozlovsky, the deputy chairman of Goskomsport, pointed out that they sent 600 premade gymnasiums for villages in 1989 only for some to be assembled in the end and used for storage.[15]

The future looked bleak for the Soviet athletic structure. It needed a spark of some kind, any kind.

Fortunately, Smirnov had a trump card holstered…

Announcing MOVLAD

April 18, 1990.

The World Trade Center in Moscow was packed as everyone awaited to hear of a new and ambitious project. Smirnov was joined by his fellow RSFSR State Sports Committee members and, more notably, Dr. Ercole Cacciami.[16]

Cacciami was the co-founder of Progress Consultant, a marketing firm created in 1978 that produced advertisements for companies like Levi’s and Kodak. Among Cacciami’s creations was the Kodak Space Light, a unique lamp he made in 1990 for customers who bought Kodak’s Ektachrome and Kodacolor Gold film reels.[17]

More pertinently, Cacciami was an avid rally driver and in Moscow on behalf of GII. Short for Gruppa Initiativo Internationale, or “Group of International Initiatives”, GII was an event organizer owned by Progress Consultant.[16] GII was eager to join the growing list of Western brands and sports entities investing in the Soviet Union under perestroika, such as the Oklahoma high school football teams that played in Moscow, Tallinn, and Leningrad in 1989 and the USSR national team touring the States a year later.

Wednesday’s announcement was the product of a year’s worth of work and prep, which began when Cacciami approached Smirnov about creating a rally only on the condition that it was “fully off-road”. Smirnov was happily onboard, and it didn’t take long for him to get the green light from the Kremlin, Ministry of Defense, and KGB.[18]

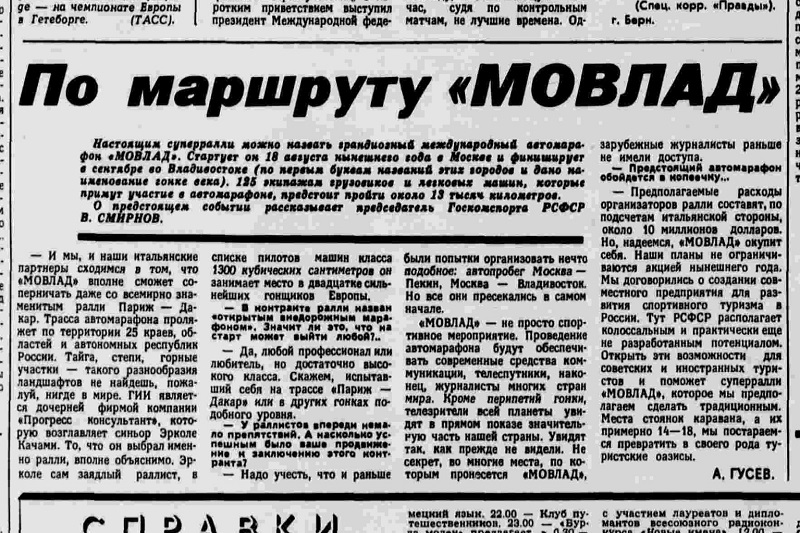

This joint effort spawned a rally raid called “MOVLAD”. A portmanteau of the start and finish points, the race would begin on August 18 at the Red Square in Moscow and finish in Vladivostok on September 8 (thus, “MOScow” + “VLADivostok”).[16][18] The route was to stretch 23 stages and 11,323 kilometers—3,198 being timed—through 25 regions and oblasts, passing a variety of ecosystems like tundra and steppes.[18][19]

Smirnov had exceptionally high hopes for the event as “not just a sporting event” but an international spectacle to showcase Russia to the world. If it worked out, he envisioned a caravan that would follow the rally and stop at 17 to 18 points as a “tourist oasis” of sort. For media coverage, MOVLAD would rely on “modern communications equipment, TV satellites, and journalists from around the world. Besides the twists and turns of the route, television watchers around the globe will see a significant part of our country as they have never seen before.”[20]

He went as far as to proclaim, “We and our Italian partners agree that MOVLAD can fully compete even with the world-famous Paris–Dakar Rally.”[20]

Likewise, Cacciami wanted to see it grow into a race worthy enough to join the FISA Cross-Country Rally Championship.[18] The predecessor to the FIA World Cup and today’s World Rally-Raid Championship, the series had been in the works for months and was set for its inaugural season in 1991 with races like the Paris–Dakar and even a new event that went through the USSR called the Paris–Moscow–Beijing.[21] The latter was organized by the French and a multinational race whereas MOVLAD was supposed to be the Soviets’ own show and solely in their own domain, so Smirnov and Cacciami were keen on getting it up to the same level, if not higher.

“I hope and believe that the Moscow–Vladivostok Rally will become a tradition and the most prestigious competition of its kind in the world,” Cacciami said.[18]

Things seemed to be trending up for Smirnov now. The day after the conference, he won the SOC presidential election with 72 votes of 110 cast.[13]

Organization

Behind the scenes, Cacciami assembled a team of Soviets and Italians. For race director, he brought in Eduard Georgievich Singurindi, then a PE professor at the Leningrad Forestry Academy and a Master of Sport who won two national rally championships.[22] Andréa Balestrieri, a Dakar bike mainstay in the 1980s, was named technical director.[18]

Since the route followed the path of the Trans-Siberian, the organizers wanted to have specially equipped trains on the railway as a mobile bivouac for teams and media.[22]

125 slots were available. Anyone could register, amateur or professional, as long as they were of a “sufficiently high class” like having Dakar experience.[18] Who specifically signed up was unknown to the Russians, though; Soviet Automobile Federation racing deputy chairman Alexander Klopichev noted the entry list was kept private and only known by GII.[22]

Multiple foreign manufacturers expressed interest in taking part such Audi, Daimler-Benz, Fiat, Peugeot, Toyota, and Yamaha.[18] On the other hand, while Lada had proven to be a competitive brand at Dakar, Klopichev shot down Soviet media speculation on whether they’d enter the production class since Poch-prepped Ladas had upgrades (300 horsepower compared to the native 150 hp, stronger suspension, etc.) that the factory back home couldn’t make.[22] A Soviet team still planned to enter with five cars, though expectations against the global juggernauts were rightly low.[18]

Klopichev was very blunt about the performance gap between the native Lada and those built by Western dealers.

“What did you expect? We have no competition between manufacturing plants,” he commented. “There’s no need for advertising when what’s produced is sold on the black market for two or three times the nominal price. Only when market principles start working—and when will this happen in regard to cars?—we can expect a change in the situation.”

Still, truck makers KAMAZ and even ZIL threw their hats into the ring.[22] MOVLAD was uncharted territory for ZIL, a legacy manufacturer that was founded during the Russian Empire and had a factory racing program but never appeared in rallies.

GII was expected to cover most of the race’s expenses, which were likely to add up to about $10 million, though Smirnov figured the race would pay for itself in due time.[20]

That due time never arrived.

Welp.

Race registration closed on May 9.[18] And then, silence.

The summer passed without any update whatsoever, making people wonder if the rally would happen. In July, Pravda reached out to the RSFSR State Sports Committee for comment and heard back from Gennady Aleshin, who oversaw the committee’s aquatic sports department and USSR Swimming Federation at the time and would later serve as vice president of the Russian Olympic Committee.[19]

Aleshin gave a straight answer: MOVLAD had been postponed to 1991.

“Our specialists have done a lot to prepare the Moscow–Vladivostok raid,” he started.[19] “The competition route has been chosen, the organizational and judging personnel have been assembled, and, at your request, organizing committees have been created along the raid’s route. The route documents have been prepared. We laid out the aviation support route and prepared support helicopter crews. However, for a number of reasons, the organizers of the competition decided to postpone the raid to 1991.”

When pressed for those reasons, he was just as frank.

GII asked the Kremlin for what Aleshin called “government guarantees” to ensure the rug wouldn’t be pulled out from under them while running the rally. While a reasonable request in Aleshin’s eyes, GII never heard back because there technically wasn’t a government when they reached out.[19]

MOVLAD had been approved by the Politburo set up by the 27th Congress of the Communist Party in 1986. When the 28th Congress met in mid-July, the previous politburo resigned from their posts to make way for their replacements. On paper, the turnover was a simple enough process that had been done plenty of times over the decades, but it was a lot more contentious this time around.

Due to the reforms under Mikhail Gorbachev, the new politburo was larger but much weaker than its predecessors. Gorbachev and his lieutenant Vladimir Ivashko were the only holdovers from the 27th Politburo, surrounded by new faces with more noticeable ideological differences. The 28th Congress had been split into different camps of varying beliefs, such as more centrist or liberal views on communism, while the voting process to form the politburo was also radically overhauled. While Gorbachev remained General Secretary, the new system would’ve made it harder to remove him than under the previous format as an entirely new congress would’ve been needed to show up.[23]

With the politburo still trying to get off the ground, GII could only twiddle their thumbs awkwardly before asking if they should come back later. ‘Later’, of course, meant trying again another time instead of the scheduled date.

“We supported them. To be honest, there was also very little time for preparation,” Aleshin added.[19] “Practically, we did everything, but why rush?”

Foreign teams soon pulled out, figuring they’ll come back in 1991 if it happened. However, some Soviet organizers and manufacturers still wanted to proceed with the original date because they had already done all the prep work needed.

After months of being left in the dark, the 1990 MOVLAD suffered its grim fate. Due to severe rain in Bashkortostan, the race would not be held.[24]

The Unofficial MOVLAD

Officially, there was no MOVLAD in August and September 1990. Unofficially…

Not wanting their preparations to go to waste, KAMAZ and KrAZ decided to bring some trucks to Moscow. It wasn’t an actual race and neither were trying to set the fastest time. Instead, it was basically a test session as they tried to see if the MOVLAD route was feasible.[24] Pravda compared it to a recce.[25]

KAMAZ opted to do just a few legs while KrAZ wanted to go the distance. The latter, a Ukrainian marque, had an experimental KrAZ-5E6315 that they built while fielding a pair of KrAZ-6322 trucks as support trucks.[24]

For KrAZ, a manufacturer with zero rally experience, the effort was a mess. While the 5E6315 was beefed up from the stock model used by the military, it fell behind KAMAZ quickly and only kept relatively close because the engine was strong enough.[26]

By the time they reached Chita, nowhere close to Vladivostok, KrAZ chose to call it quits when they ran out of driveshafts. The truck was eventually sold and turned into a tractor, then to an oil refinery in Kremenchuk as a fuel transporter.[26] KrAZ would eventually return to the rally world in 2008 with an attempted Dakar entry, but that was out of the picture when the race was canceled.

It wasn’t much easier for KAMAZ, who dealt with a myriad of broken spring and tire failures amid the muddy conditions. Still, they made it to Krasnoyarsk and Lake Baikal safely.[25]

An Alternative Rally

To no surprise, MOVLAD failed to happen in 1991 as well. However, Moscow didn’t have to wait long for a substitute. In fact, this one beat MOVLAD to the punch.

In February 1990, three-time Dakar winner René Metge and Mitsubishi announced the creation of the Paris–Moscow–Beijing Rally. It was a quasi-revival of the Peking to Paris that took place in 1907, after which re-enactments couldn’t happen under Soviet rule. Unlike MOVLAD, which Smirnov and Cacciami wanted to get going just four months after their conference, Metge was more reasonable and put the inaugural start date on September 1, 1991.[27]

The Paris–Moscow–Beijing was put on by French organizers via the Fédération Française du Sport Automobile with less Soviet government involvement (which makes sense since it crosses multiple countries).[28] That wasn’t to say that the Kremlin didn’t have a role as they signed a contract in November 1990 with Mitsubishi through Sovintersport, a state agency created four years prior to let Soviet athletes compete abroad.[29]

“It is of great interest not only among professionals and amateurs of motorsport, but also in the business world,” Pravda remarked.[29]

Ironically, this was also postponed for political reasons as the August Coup took place against Gorbachev. Originally, Metge wanted to push it back two weeks and Klopichev was willing to accommodate, saying that “all our support services were ready.” However, Egyptian officials felt the date change would make it hard for the top teams to make it to the Rallye des Pharaons afterward, so Metge stood down.[30]

By the time the Paris–Moscow–Beijing finally took place in 1992, the Soviet Union was already a thing of the past.

References

[1] “1956 Season Review” by Aleksey Rogachev, Автоспорт в СССР

[2] “ВТОРОЕ МЕЖДУНАРОДНОЕ АВТОМОБИЛЬНОЕ РАЛЛИ «РУССКАЯ ЗИМА»” program, 1966

[3] “Jyväskylän Suurajot 1958 entry list”, eWRC-results.com

[4] “Как «Москвич» покорил весь мир. От Лондона до Сиднея — без единой поломки” by Lev Dorogov, Чемпионат

[5] “Daily Express London-Sydney Marathon 1968 results”, eWRC-results.com

[6] “Парижские старты «Лады»” by Ivan Shchedrov, Pravda, January 2, 1986

[7] “Из Парижа в Дакар” by Sergei Filatov, Pravda, January 17, 1990

[8] “Смирнов считает, что бойкот США Игр в Москве повлиял на решение СССР не ехать на ОИ-1984”, TASS, August 3, 2020

[9] “Как СССР решился на бойкот Олимпиады-84 в Лос-Анджелесе? Рассказывает Виталий Смирнов – участник тех событий” by Natalia Maryanchik, Sports.ru

[10] “The Cold War and the Olympics” by Allen Guttmann, International Journal Volume XLIII, Autumn 1988

[11] “IOC sharply divided over boycott penalties” by the Associated Press, The Daily Breeze, December 2, 1984

[12] “Long Lines Common In Moscow” by National Geographic, April 4, 1990

[13] “Smirnov Elected Committee President”, Indian River Press Journal, April 20, 1990

[14] “Soviet supremacy is under threat” by Neil Wilson, The Independent, April 12, 1990

[15] “Perestroika Stops at the Medal Stand” by Randy Harvey, Los Angeles Times, April 17, 1990

[16] “РАЛЛИ: СССР ПРОДАЕТ СВОЕ БЕЗДОРОЖЬЕ”, Коммерсантъ Власть volume 15, April 23, 1990

[17] “Ercole Cacciami, Kodak Space Light, Progress Consultant 1990”, The Neuter

[18] “«МОВЛАД»: ПРОБЕГ ПО БЕЗДОРОЖЬЮ” by I. Andreev, Izvestia, April 23, 1990

[19] “Пауза на трассе «Мовлад»” by A. Kolesnikov, Pravda, July 23, 1990

[20] “По маршруту «МОВЛАД»” by A. Gusev, Pravda, April 18, 1990

[21] “FISA plan three-race world cup for rallies”, The Daily Telegraph, December 7, 1990

[22] “ГОНКА НА ГРАНИ ВОЗМОЖНОСТЕЙ” by A. Kolesnikov, Pravda, May 25, 1990

[23] “Gorbachev strips Politburo of top officials” by the Associated Press, The Daily News, July 15, 1990

[24] “Гонка без соперников: как в СССР хотели устроить свой «Париж-Дакар»” by Ivan Panin, June 29, 2020

[25] “Это вам не Сахара…” by A. Kolesnikov, Pravda, September 3, 1990

[26] “Ралли Москва–Владивосток ’90 глазами команды КрАЗ” by Ivan Panin, June 29, 2020

[27] “Round Up”, The Daily Telegraph, February 16, 1990

[28] “Raid an historical link”, Cambridge Evening News, December 20, 1991

[29] “Готовы купить команду” by P. Vasilyev, Pravda, November 12, 1990

[30] “Ралли-рейд «Париж-Москва-Пекин» откладывается”, Auto Motor und Sport issue 4, 1991

Featured image credit: KAMAZ History Museum

Leave a comment